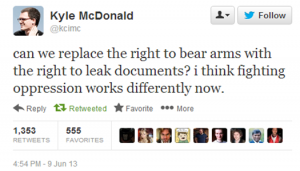

Last week, I suggested that the U.S. might benefit from seeking leaking as a useful tool to support democracy in a nontransparent age.

This week, rather than setting up the two as opposed, I want to begin from the premise that what the NSA’s PRISM surveillance and the leak that revealed it have in common is that they were undertaken with the belief that the ends justify the means.

First, under the logic of democratic transparency I described last time, it would seem clear that people had a right to know what was happening, but did the means justify that end? Leaker Edward Snowden obviously thought that it did. He claims that his “sole motive is to inform the public as to that which is done in their name and that which is done against them,” disregarding the means necessary to achieve it altogether as he maintains, “I know I have done nothing wrong” (Guardian).

(Jeremy Hammond, who hacked a private security firm to expose its manipulation of public opinion, said much the same thing)

The Atlantic’s Bruce Schneier also prioritizes the leak’s ends, actively encouraging further leaking: “I am asking for people to engage in illegal and dangerous behavior. Do it carefully and do it safely, but — and I am talking directly to you, person working on one of these secret and probably illegal programs — do it.”

Others, however, think that the ends don’t justify the means. This I think is where you get polling data that both say Snowden did the right thing and that he should be punished.

WikiLeaks documentary director Alex Gibney, interviewed in The Atlantic, makes a similar argument that both values the ends and attaches consequences to the means with regard to leaker Bradley Manning: “you have to acknowledge that he broke an oath to the military, and we wouldn’t want a world, at least I wouldn’t want a world, in which every soldier leaked every bit of information that he or she had. Manning broke an oath and he’s actually pled guilty to it, and he’s willing to face the consequences.”

At the far end of the spectrum from Snowden’s complete focus on ends, Director of National Intelligence James Clapper (predictably) doesn’t even consider the possibility of value in the ends, contending that “Disclosing information about the specific methods the government uses to collect communications can obviously give our enemies a ‘playbook’ of how to avoid detection” (Washington Post)

There is also an ends vs. means question on the surveillance itself. It’s quite possible that people are actually being protected by this blanket surveillance. Maybe fifty plots have really been foiled. Certainly, having people not blown up is an admirable end. But at what cost? A case could be made that the means are destroying the very freedoms they’re intended to secure.

My concern here is in the minority. There has been some significant nonchalance about these surveillance revelations, such that it seems people are ok with the surveillance means out of support for its ends. A Pew Research Center poll found a majority saying tracking phone data was acceptable. Daniel Solove’s Washington Post piece sought to dispel privacy myths like “Only people with something to hide should be concerned about their privacy.”

The NSA unconcern may seem like a startling abdication of privacy, but is actually a relatively prevalent attitude. As Alyson Leigh Young and Anabel Quan-Haase argued in their recent article on Facebook and privacy, people (undergrads, in their sample) are generally much less worried about institutional privacy issues like corporate or government surveillance than they are about social privacy (their mom or boss seeing their drunk party photos).

Jan Fernback, in a post at Culture Digitally, similarly argues that “when thinking about appropriate information flows, surveillance contexts, and notions of ethics and trust, we must distinguish the legal dimensions of privacy law from the social dimensions.”

Ultimately, the different things that are being evaluated against each other in this case may be operating in such different registers from each other that they’re incommensurable. As Fernback notes, “privacy opponents argue that we need surveillance to catch wrongdoers while privacy advocates argue that surveillance harms individuals. How do these contexts differ? What good is being served? What interests are being weighed? Is trust being violated? What power imbalances are evident? What technical regimes are implicated? How is information being used?”

It’s this sort of calculus that has to be used to really parse the ends and the means. Under this view, then, one problem with surveillance as a means is that, as Moxie Marlinspike argues in Wired, “we won’t always know when we have something to hide.”

They quote one of Supreme Court Justice Breyer’s opinions describing “the complexity of modern federal criminal law, codified in several thousand sections of the United States Code and the virtually infinite variety of factual circumstances that might trigger an investigation into a possible violation of the law.” People don’t always know what’s illegal. Or, things previously legal may become illegal. (This invites the argument that “ignorance of the law is not an excuse,” but when laws are so voluminous and often nonsensical it’s hard to hold the line on that.)

Or, the opposite: things that were previously illegal may become legal, but—as Marlinspike points out—we can’t agitate to change those laws without being able to break them and see that they shouldn’t exist. The Wired piece uses the examples of marijuana legalization and same-sex marriage, and we can think of others, but if there was perfect surveillance, forget about any of it.

These means, that is, have many extenuating consequences that we have to balance against their ends. And, to circle back a bit to last week, that’s why there has to be transparency, so that we can work through what those consequences are and see whether the ends are justified, as much for the leaking as the surveillance itself. We simply can’t assess these programs unless we know how they work.

For the first time in this blog’s history, this topic has produced a three-parter. Stay tuned next week for a consideration of due process.