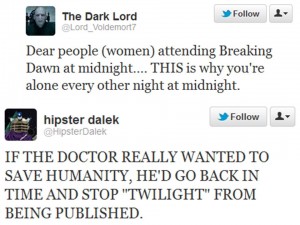

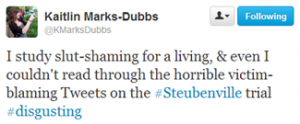

There has been a ton of writing about all the wildly awful things about the Steubenville sexual assault case: the slut-shaming and victim-blaming;  the focus on the boys’ “ruined lives” at the expense of any mention of the impact on the person who experienced the assault;

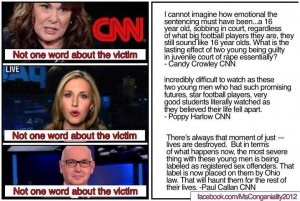

the focus on the boys’ “ruined lives” at the expense of any mention of the impact on the person who experienced the assault;  CNN’s bizarre coverage (which prompted petitions to land in my inbox from three separate progressive organizations); and all the awful things that got said on social media (brought to my attention by @AmandaAnnKlein). Also, there was a truly odd use of the word “alleged”–its purpose is for the perpetrator, to preserve “innocent until proven guilty,” not for the victim, to imply nothing ever happened, mmkay?

CNN’s bizarre coverage (which prompted petitions to land in my inbox from three separate progressive organizations); and all the awful things that got said on social media (brought to my attention by @AmandaAnnKlein). Also, there was a truly odd use of the word “alleged”–its purpose is for the perpetrator, to preserve “innocent until proven guilty,” not for the victim, to imply nothing ever happened, mmkay?

All of those things have been critiqued, I think, extraordinarily well, and I don’t think I can improve on that.

What I want to talk about is the ways this may be a turning point for electronically networked youth culture.

This is not to suggest, as some journalists have, that somehow the events are a product of electronic networks, as with Susanna Schrobsdorff’s statement in Time: “Joking about rape, referencing sexual acts and girls making fun of girls perceived as ‘sluts’ is just part of teen online culture now.”

This is not part of teen online culture. It’s part of teen culture, full stop. And it’s not “now”; as someone who presumably went to high school more recently than Schrobsdorff, I can vouch that saying these kinds of awful things is not new. What’s new is the visibility, the leaving of traces.

I’m a scholar of gender and sexuality and media; lots of people in my circle account themselves feminists. And as a result, an interesting juxtaposition occurred on my Twitter feed during the week of March 18: Veronica Mars and Steubenville. (I was late on Veronica Mars because of SCMS, and now I’m late on Steubenville because Veronica Mars broke first. A day may come when a news event will coincide with my blog production cycle, but it is not this day.)

But watching the last couple episodes of Season 1 of Veronica Mars the other weekend (in which, spoiler alert, Veronica finally pieces together what happened the night she was drugged and raped) in conjunction with the verdict in the Steubenville case coming down, there were both such similarities between the fictional case and the real one and such crucial differences that it got me thinking.

In VM, as in Steubenville, lots of people witnessed sexual things happening to a drugged girl who everyone assumed was drunk and slutty. All of those witnesses (with the exception of the ex-boyfriend in the VM case), did not act to stop the events from occurring, which makes them morally responsible even if legal codes often don’t have a way to make such bystanders criminally responsible. (Though, you know, bystander effect is a real thing that happens.)

When Veronica could not remember what happened, and knew only that something had, it took her a year of piecing together disparate sources to figure it out. In Steubenville, electronically networked youth culture recorded everything, and though the local authorities were not inclined to intervene until prodded by national outrage and Anonymous, those (prosecutable) traces made the difference. As Richard Oppel wrote in the New York Times, “because the victim did not remember what had happened, scores of text messages and cellphone pictures provided much of the evidence” in the trial.

The fictional bystanding and the subsequent harassment of Veronica as slutty took place in meatspace, was ephemeral, left no traces. The parallel with the real-life crime is that “the trial also exposed the behavior of other teenagers, who wasted no time spreading photos and text messages with what many in the community felt was callousness or cruelty” (Oppel).

At SCMS a few weeks ago, I attended a paper on bullying in Nickelodeon TV show iCarly, given by my colleague Martina Baldwin. One thing that came up in the Q&A after the session was that, while there’s a long tradition of young people being awful to each other, the difference is in the traces. Things that used to be said in hallways and heard by only a few people now last longer because they are written down; by comparison to the nasty note written on paper, the text message or Facebook posting is exponentially more transmissible and harder to destroy. (Of course, this is the paradox of the Internet: things you want to get rid of last forever; things you want to preserve disappear.)

Indeed, the moral panic around “cyberbullying,” while technologically deterministic in suggesting that such things never occurred before the Internet, may not be totally off base. First, there’s the increased nastiness that comes with not bullying someone in person (this is not just true of youth; see the comments on any news story with a controversial topic, many if not most of which are written by adults). Second, there’s the intensification that comes with the seeming permanence and “everybody knows” aspect of these modes of harassment.

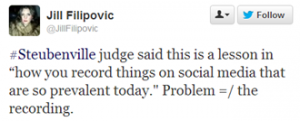

But now, the people who did not assault the girl physically but did do so emotionally and socially may also face consequences. The Ohio attorney general has announced that he “might consider offenses that include obstruction of justice, failure to report a felony and failure to report child abuse” (Oppel). This is an interesting turn of events, and not for the reason suggested by what the judge apparently said:

include obstruction of justice, failure to report a felony and failure to report child abuse” (Oppel). This is an interesting turn of events, and not for the reason suggested by what the judge apparently said:

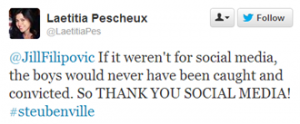

(Which sounds a bit like “you would have gotten away with it, too, if it weren’t for those meddling kids.”) While it may indeed serve as a lesson to kids to keep their torture of each other more private, it also has another potential:

Youth culture is, more or less, what it has been—if not always, at least as long as I’ve been aware of it. It was already highly networked and skilled at the transmission of information, particularly in ways that harass and harm others.

But the fact that the youth network is now electronic made all the difference in securing justice for that girl in Steubenville. Even more broadly, the use of electronic media traces as evidence in prosecution raises the possibility that the unique ways that these technologies intensify the awfulness of teen culture may begin to recede. In this way, despite all the ridiculousness that has surrounded it (see again the first section of this blog), the verdict is an incredible step forward.