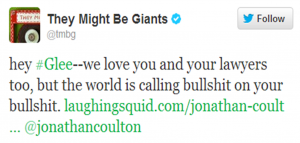

I first saw the story on January 19, retweeted to me by @kouredios from the Twitter of band They Might be Giants:

Briefly, independent artist Jonathan Coulton covered Sir Mix-a-Lot’s “Baby Got Back” in a distinctive style, and Glee’s cover of the song is virtually identical to Coulton’s, causing uproar from pro-Coulton and anti-Glee forces on the Internet under the hashtag #JoCoGleeGate. Both Coulton and Glee licensed the intellectual property of the song—the lyrics—from the appropriate parties, but Glee did not license Coulton’s arrangement from him, nor even inform him before recording and releasing the song.

This series of events seemed unfortunate, of course, but it didn’t arrest my attention at first. Until it made it to CNN a week later:

This series of events seemed unfortunate, of course, but it didn’t arrest my attention at first. Until it made it to CNN a week later:

By the time Mythbusters co-host and geek-chic internet celebrity Adam Savage got into it on January 28,  I had also gotten around to reading Casey Fiesler’s 2008 piece Everything I need to know I learned from fandom: How existing social norms can help shape the next generation of user-generated content, and I knew I needed to write about it.

I had also gotten around to reading Casey Fiesler’s 2008 piece Everything I need to know I learned from fandom: How existing social norms can help shape the next generation of user-generated content, and I knew I needed to write about it.

What we see from Glee’s decision and the ensuing (mini)scandal is the way in which the copyright system fundamentally fails at distinction. To reuse the quote from Fiesler that was my structural guide last week, “at one end is completely original material (no threat to copyright owners), and at the other end is wholesale copying (obvious infringement)” (p. 757), and the huge gray area in the middle is where current copyright law has no answers.

This is because anything other than “no threat” gets collapsed into “completely owned by the original rights-holder.” As Fiesler explains earlier in the piece, “legally, only copyright owners have the right to prepare [derivative] works. This applies to anything from the slightest modification to something so transformed that the original is hardly recognizable” (p. 737), which are, in the eyes of the law, all equally derivative.

Though Fiesler argues that “derivative works are transformative; basically, they incorporate copyrighted aspects of the original without being carbon copies of the original” (p. 737), that is, it’s actually the case that the transformativity or “adding new material” aspect is not something the law can account for very well, and this needs to be taken much more seriously.

Fiesler relegates the point to a note: “as it stands now, if, for example, someone attempted to profit from someone else’s fan fiction, the original fan fiction writer would probably not have a legal remedy, as they did not hold the copyright in their work in the first place” (759 n. 182), but it’s a pretty big deal. After all, it’s pretty much exactly what happened to Jonathan Coulton in a different medium.

Coulton added significant aspects to the song, but because it was based on another source song, he would seem to have no legal claim. As CNN explained, “the rights to ‘Baby Got Back’ belong with songwriter Anthony L. Ray, also known as Sir Mix-A-Lot, and his music publisher, Universal, who have apparently given proper licenses to Fox and ‘Glee.’” Coulton, despite his contribution to what Glee ultimately produced, does not factor into the equation at a legal level. He didn’t own the words, so he seemingly loses his claim to the music as well.

If that seems messed up to you, you’re not alone. Though Coulton apparently has no legal standing, he does have a moral one. It’s obvious to everyone that Coulton’s creativity went unacknowledged in this process, and as Adam Savage’s call to action quoted above suggests, people are rallying behind Coulton to the degree that his version is outselling the Glee cast recording:

If that seems messed up to you, you’re not alone. Though Coulton apparently has no legal standing, he does have a moral one. It’s obvious to everyone that Coulton’s creativity went unacknowledged in this process, and as Adam Savage’s call to action quoted above suggests, people are rallying behind Coulton to the degree that his version is outselling the Glee cast recording:

The irony that it should be Glee, with its track record of supporting diversity (albeit in a sanctimonious, oversimplified way), that’s stomping on a small-scale music maker has also not escaped anyone. As Coulton complained in the CNN piece, “Glee has a reputation for being a show that celebrates the underdog [ . . . ]. It’s the anti-bullying show. But this is a bullying way to approach this.”

(Of course, Glee is a product of a massive media empire, and no one would be surprised by Rupert Murdoch bullying anybody, which is a whole other bait-and-switch and reputation-scrubbing issue.)

But regardless, the lawyers at Fox presumably knew the lay of the legal land, and knew they could get away with it either because they’d win in court, possibly immediately because there’s no standing in copyright law for Coulton, or because they knew Coulton didn’t have the financial wherewithal to sue them in the first place. Either way, it’s ultimately the weird ways that copyright has become wildly top-heavy that are at root here. So much for underdogs.