Last week, I talked about the various economic and legal issues involved in Kindle Worlds, like unpaid labor, extraction of value, fair use, and ownership of one’s own creative products. (And that’s what you missed on Glee!)

And now, for the exciting (and quite long) conclusion, a discussion of the cultural issues at stake.

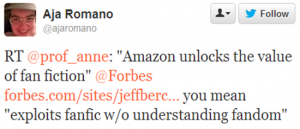

One recurring comment about Kindle Worlds is that it is set up in a way that suggests a lack of understanding of fandom, as in this comment from Aja Romano (via @bertha_c):

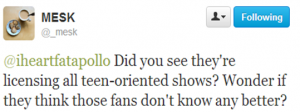

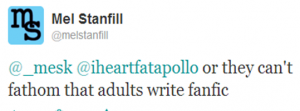

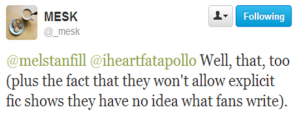

Or this exchange between Melanie Kohnen and me:

The question “Is it really fanfic?” has repeatedly been raised, with Karen Hellekson noting that “if you define fan fiction as ‘derivative texts written for free within the context of a specific community,’ then this isn’t that. True, they are fans. And they write… fiction. But what Amazon Worlds is doing is extending the opportunity to writers to work for hire by writing, on spec, derivative tie-ins in a shared universe, under terms that professional writers would be inclined to reject.”

Noah Berlatsky of The Atlantic playfully noted that “you could even say that Amazon is turning the term ‘fan fiction’ into fan fiction itself, lifting it from its original context and giving it a new purpose and a new narrative, related to the original but not beholden to it.” John Scalzi also questioned whether it’d qualify as “fan fiction,” deciding that it is and it isn’t.

However, some fannish commentators have been in favor of Kindle Worlds, untroubled by these factors, such that they might also, paradoxically, be open to the charge of not understanding fandom. Rebecca Pahle, writing for The Mary Sue, noted that some may be upset that “giant corporations (the publisher of Gossip Girl, Pretty Little Liars, and Vampire Diaries is owned by Warner Bros.) will be making money off of the labor of their fans. That’s not a viewpoint I share, though, because that’s what happens anyway: Fans put thousands of hours of effort into creating fic, graphics, crafts, etc., expecting nothing in return other than the object of their fandom being good,” adding that “I for one want to see more authors earn money off of it.”

At OTW Fannews, Curtis Jefferson noted that while some are “concerned about what this development will mean for fanfiction communities, though the less they know about them, the more likely they think of Kindle Worlds as a great development.”

As suggested by Jefferson, acceptance or rejection of Kindle Worlds seems to be related to whether people are embedded in the community. Now, there isn’t really just one community, but people who have been in fandom for a while, and in several fandoms over time, have been exposed to and/or acculturated into a set of practices and values that has had some continuity.

In that very limited sense, as an amorphous and internally heterogeneous thing, “the community” singular isn’t totally unreasonable. It’s an imagined community rather than an actual set of interconnections among the people. In fact, assume scare-quotes on it going forward.

One main part of this norm is that fandom in general and fan fiction in particular should be noncommercial. This is an ideal rather than a fact; as Kristina Busse noted in an email exchange in which I participated, “I think the longer I’m in fandom, the more I see that the economies always have overlapped,” and Pahle’s point above gestures toward this, too. Fandom isn’t isolated from market values, not least because it tends to respond to capitalist-produced media.

But normatively those things have traditionally been kept apart, as shown by the extensive work on gift economies in fandom (some of my favorites: Hellekson’s A Fannish Field of Value: Online Fan Gift Culture and Suzanne Scott’s Repackaging Fan Culture: The Regifting Economy of Ancillary Content Models).

Part of this is that fans understand themselves as getting other, nonmonetary benefits. As Livia Penn put it, “I keep seeing people saying ‘you’ll get 20% to 35% of the profit. And that’s better than nothing!’ (Well, sidebar: I don’t get ‘nothing’ from writing fanfic. If you’re not a fanfic writer who shares their fic with a community of readers, it would take me another two thousand words to explain what you *do* get, but trust me. It isn’t nothing.)”

Scalzi likewise notes that “there’s a difference between writing fan fiction because you love the world and the characters on a personal level, and Amazon and Alloy actively exploiting that love for their corporate gain and throwing you a few coins for your trouble.”

So there has to this point been a fan community with some (rather) loose norms about how fiction works, among which are a non-monetary system of reward and exchange and a relationship to industry somewhere between wary and hostile. This is what fan scholarship has long described, due substantially to the fact that two generations of scholars (maybe two and a half or three) have been to varying degrees embedded in this community. This comes out of the founding of fan studies as a project of fan-scholars wanting to speak for themselves and their own community.

But I am beginning to wonder if the community, already minoritized in the world at large and within fandom, might also become minoritized in fan fiction itself. That is, while Kindle Worlds is not fan fiction as it has been, it might be fanfic as it will be.

Generational turnover in the population has happened, and from my own limited and anecdotal experience, younger fanbases are often not within the tradition. I don’t know if they know it exists and have rejected it; or the influx of fans was too great to teach them all how it had been done before; or they don’t know at all because searchability provides different routes to finding out that there is such a thing as fic in the absence of knowing how it has traditionally been done. (Actually, can someone do the research and find out why, plzthx?)

So, this generation shift is one route by which we may see the end of fan fiction as we know it. It seems to me that the proportion of writers that aren’t within the tradition is steadily rising: lots of fic I am seeing doesn’t use beta readers, the reciprocity of feedback as payment for creativity is decaying, some of the old rules about acceptable content have vanished, etc.

I take no position on whether this is shift in the normative way of writing fic is good or bad. I like the tradition, and I think it is valuable, but I’m not one for prescribing how people go about doing things that give them pleasure. However, I do think it’s important to consider carefully whether this is a large-scale change and think about its implications.

I also have to wonder if the fact that most of the scholarship has been done by people embedded in the tradition might be why we haven’t seen this coming. This isn’t to critique those people or their work per se (and indeed there is some recognition that there are other ways, as with Busse’s comment that “maybe there is a market–it just won’t be ours, I think”) but rather to point to the tradeoff that every angle of vision makes some things more visible than others.

Related to this question of generations and fannish continuity, the comparisons of Kindle Worlds to the 2007 for-profit fan fiction archive FanLib were not long in coming. Scott asked whether fandom would “respond as quickly/vehemently this time around,” and I think that the (potential) ongoing generation shift has to be taken into account in answering any such question. Has fandom hit a tipping point (which it hadn’t at the time of FanLib) over into a critical mass of people who will see this as legitimate? That will, I think, be the deciding factor.

That point of contact, between fan norms and industry action, is the other place to think about the end of fan fiction as we know it. The practices and populations seem to be changing, or at least new ones are being added, and only some versions are being built into industry logics.

Kindle Worlds, like many other projects at this historical moment, is about–as Jenkins, Ford, and Green parse the distinction in Spreadable Media–“’fans,’ understood as individuals who have a passionate relationship to a particular media franchise,” not “‘fandoms,’ whose members consciously identify as part of a larger community to which they feel some degree of commitment and loyalty” (p. 166).

What I want to suggest is that Kindle Worlds is part of a broader shift to incite fans-the-individuals to ever-greater investment and involvement but manage them though disarticulating them from the troublesome resistive capacity of fandom-the-community.

On one hand, this is part of the monetization of everything. As Busse commented, “I think the thing that unsettles me is when copyright holders ask us to create material to sell it back to us,” which she noted is something that “many of the recent fan studies works have all but explicitly encouraged them to do.” Or, more snarkily, “Don’t you know that things don’t exist until some dude somewhere makes money off it?”

But there is also a sense in which industry is defining this (and maybe only this) as fan fiction, despite the fact that it’s not the only way and traditionally hasn’t been the primary way. As Hellekson notes, “‘work for hire, on spec, for certain tie-ins’ doesn’t really have the ring of ‘fan fiction,’ does it? By using the term fan fiction, they are shorthanding their future writers as well as their perceived audience.” That “shorthanding” stakes a claim on those writers and readers.

And that claim has weight as a definitional move, as is clear from Sean P. Aune’s wondering at TechnoBuffalo (via OTW Fannews) “if the studios that license the properties will continue to allow fans to publish their works for free around the Web. In theory not much should change, but there is now a financial stake in this sub-section of fandom where companies can earn money from the work of others, so there might be an incentive to drive people towards the pay version of fan fiction.”

Or Betsy Rosenblatt, chair of the legal committee of the Organization for Transformative Works, who noted to Wired that the narrow range of acceptable content in Kindle Worlds “underline[s] the importance of unrestricted fan platforms, like OTW’s Archive of Our Own, which ‘allow fans to express the full range of their creativity and appreciate the creativity of other fans through fair use.’”

Scalzi puts it in broader context: “I suspect this is yet another attempt in a series of long-term attempts to fundamentally change the landscape for purchasing and controlling the work of writers in such a manner that ultimately limits how writers are compensated for their work, which ultimately is not to the benefit of the writer. This will have far-reaching consequences that none of us really understand yet.”

I am not familiar enough with the landscape of professional writing to assess Scalzi’s point in that context, but there does seem to be a creative consolidation going on (alongside a small-scale proliferation enabled by technology), wherein ever more aspects of creative production are coming under the umbrella of corporate ownership and authorship rather than an individual creative person and a corporate production and distribution apparatus. And that bears thought, for fandom and beyond.

2 Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] Last summer, Amazon launched its Kindle Worlds imprint, a publishing arm dedicated to publishing commercialfan fiction. […]

[…] Last summer, Amazon launched its Kindle Worlds imprint, a publishing arm dedicated to publishing commercialfan fiction. […]